Preview of Unseen Wrath

Prologue

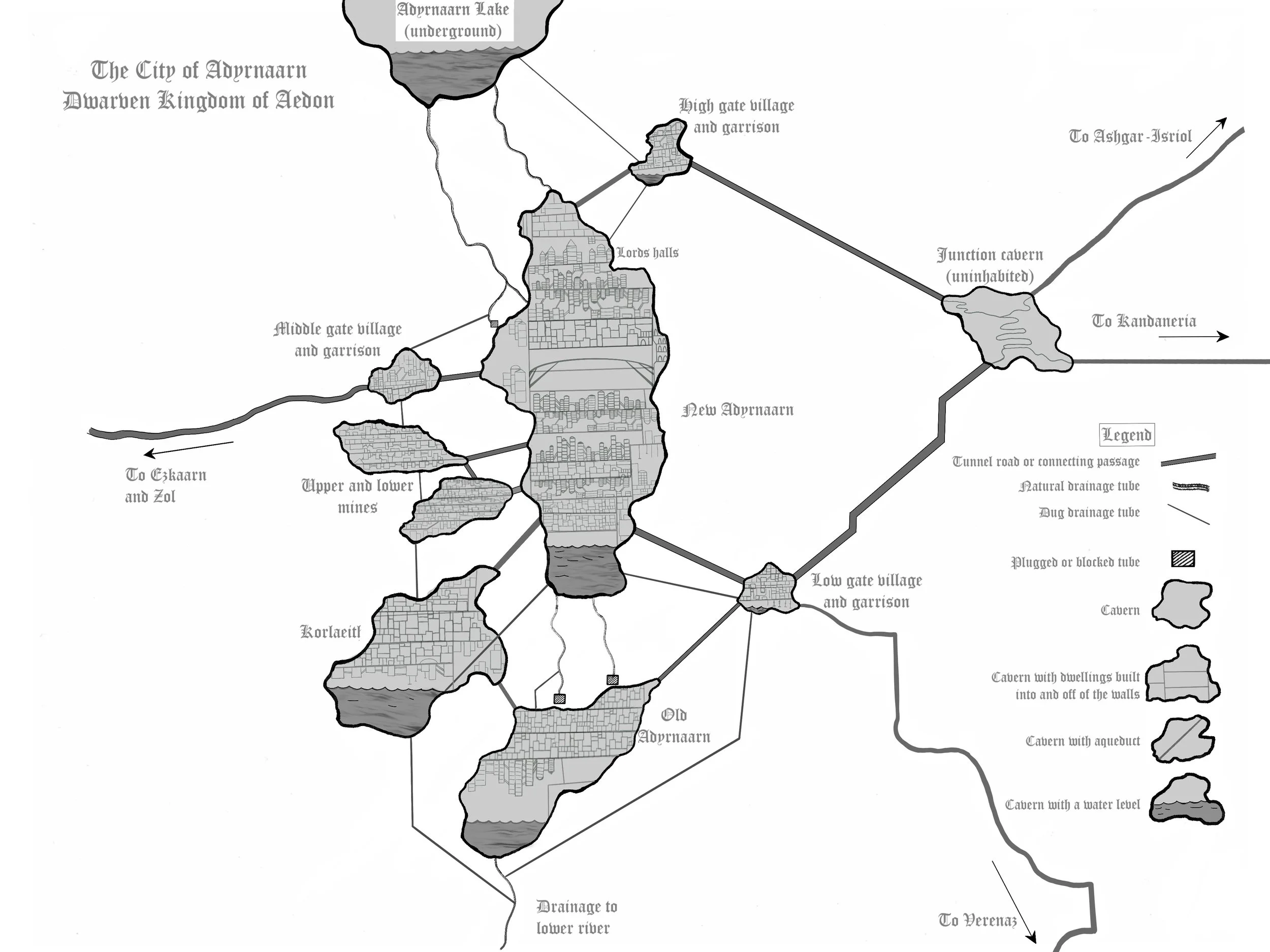

Two miles beneath the surface, deep in the Kaskev Mountains

Junction cavern near the Aedon Dwarven City of Adyrnaarn

By the Dwarven Calendar, 122nd day of the 10484th Year

By the Human Calendar, Twosday, 1st week of Darri, 794

The columns of dwarves marched forth from the mouth of the road tunnel and into the cavern, passing Gudreka, as the strength of Drenia’s legions coiled into it.

“Gudreka!” Gudreka internally shuddered. He knew that voice. He knew exactly who it was coming from. He knew exactly what that person wanted. And he knew exactly the conversation he was about to have. And yet, he was duty bound. He moved back the broad mouth of the tunnel road towards the voice that would not wait.

“Yes, Lord Therog, my general,” Gudreka saw his commander.

“There you are, mud vein. Have the pioneers mark the encampment,” General Therog commanded.

He already had the pioneers make the markings, post sentries, scout further ahead, start the cook fires, and a litany of other tasks necessary to move an army.

“Yes, my general,” Gudreka bowed.

“And post sentries! Even a mud-vein like you should have thought of that! Why do I have to tell you everything?” Therog walked past.

“Yes, my general,” Gudreka remained bowed until he passed from Therog’s immediate presence before trotting off to the side under the pretense to accomplish tasks that were already done. I have a bad feeling about all o’ this, he grumbled darkly. He looked about the large cavern. Its ceiling soared overhead, slashed with striations of hard rock. The walls were dry and there were no spikes from the ceiling for floor where water dripped and built up minerals. The road tunnel entered the cavern near the floor, but there was a road built up to the entrance of a higher road tunnel entered the cavern. That would be the road to Ashgar-Isriol. Gudreka closed his eyes. He could hear Therog’s voice in his head demanding that his legions be the ones smashing the gates of Ashgar-Isriol, nevermind that the King wants Adyrnaarn as a way to Ezkaarn and Zol. The king wanted to cripple the scheming Aedons for invading Drenia while Drenia was fighting to regain what the Medrians had stolen from Drenia a hundred floods ago.

Therog wanted to impress the king so much that the king would shower praises, titles, and lavish rewards upon him, which was not particularly strange for any of the generals in King Nerim’s grand army. The problem with Therog was his method, which was to achieve things that were not asked of him. Gudreka supposed that it might make sense to Therog in his own head, if Therog assumed that he would also accomplish what was asked of him, namely the conquest of Adyrnaarn, Ezkaarn, and Zol and to prepare for other legions to march through and conquer a weakened Aedon.

How did I find myself with this idiot? Gudreka asked himself as he moved about the growing camp and supervised the dwarf captains settle their companies in the places marked for them by the pioneers. But he knew that answer. He knew it well. No one could say when this all started a bit more than two flood seasons ago. King Nerim sent a bundle of decrees about. He reminded us all of what we had lost. What was taken. What was owed. Gudreka remembered some of those times, himself. While not old for a dwarf, Gudreka was not young, either. Having a hundred and twenty three flood seasons in his time, he remembered the sprawling mines and furnaces of Mezar Rin and Rael Dol-Buen. He remembers when Drenia lost them to flood and those thieving Medrians came with false kindness to buy the value of gold with handfuls of copper. Soon after, the Medrians built Ren-Gol and the other new border towns.

Gudreka remembers well before the orcs took Ikria. The throne did nothing, the high born did nothing and Drenia was left to soak in its shame as even orcs spat on Drenia. Gudreka nearly cried when the levies came. Finally, he remembered the joy he felt as the forges were called to stop to hear the king’s decree. The quotas were filled entirely by volunteers and the recruiters had to turn many back. ‘Someone had to run the forges and farm the mushrooms and the hogs,’ the highborn said.

Well before the next flood, Drenia marched into Ren-Gol only to be surprised. It was not only the Medrians that cheated. They had conspired with Aedon and Dranomar. As Drenia reached to take back its rightful possession, the thieves of Aedon and Dranomar pressed on Kerolus and Grednir, itself.

‘Better to take on all the thieves at once,’ the highborn had said, but Gudreka knew what this really was. This was just like a knife fight behind a drink hall, when three come at you the only way to win is to fight harder, cut deeper, show no mercy, and make no mistakes. The king raised more legions and Gudreka marched back out of Medria and into Aedon. It was not until they broke the gates of Kandaneria and several of Gudreka’s superiors had died to taken serious injury that he was promoted directly under General Therog. He had written back to his wife in Goroboln. She was overjoyed, herself. She had written back about how she bragged that her husband was a major captain under a general and what a chance it would be for them.

What a chance, he chuckled bitterly. What chance?

“Major Captain?”

Gudreka roused himself from his bleak reverie to see one of his scouts, his senior scout, in fact. A younger dwarf with a beard that strained to reach below his neck. He wore lighter armor of boiled hog and orc hides and boots of the same. His steel-spined crossbow creaked on its leather sling over his shoulder.

“Ah, Rangli. Report.”

“Thank you, Major Captain. It is as you said. No water here,” said Rangli.

“Eh, that’s fine, it is, what about the banners on the gate?” asked Gudreka.

“Ahm,” Rangli shifted uneasily, “there were a few, but there was one with a downward axe on it.”

Gudreka’s eyebrows crept up his forehead, “the King of Aedon, is it?”

Rangli nodded. Gudreka blew out through his mustache. What a chance…

“Is the banner on both gates?” Gudreka asked. He had to be sure.

“That it is, major captain,” Rangli said.

“Right. Go on, then. Fetch me the quartermaster and the master engineer. We’ll have to fix the water problem ‘afore setting into the siege,” Gudreka unconsciously cast his gaze to the far end of the cavern, toward the ramps for the tunnels to the upper and lower gates of Adyrnaarn.

“Yes, major captain,” Rangli moved off to find the two officials while Gudreka walked towards the gate tunnels. The scouts had already cleared out the sentries from the Adyrnaarn guard, but there was no real hope of surprise in any case. They would have known about the legions’ approach for a few days by now. Without water, the siege camp would have to catch water at the last stream, two days’ march to the rear and move it up… I wonder if we could be puttin’ them in the same problem. Hm. Gudreka looked over the rock striations on the ceiling.

Gudreka was roused from contemplation again as the quartermaster and the engineer found him. He gave them instructions to the quartermaster begin shuttling the water. For the engineer, he was to come up with plans for digging to the Adyrnaarn water source and for constructing a rude kind of aqueduct to the stream to determine which would be more efficient. Gudreka had formed the basis of a plan to break the gates of Adyrnaarn, but it required time.

Time to get the ugly business on, he thought after he dismissed the other two dwarves. He looked about and found General Therog’s banner, marking his location, a red banner hanging downward with the embroidery in the middle of three gold medallions arranged into a triangle. He moved towards the banner, neither rushing nor dragging his feet. Gudreka knew the next conversation would be important. And difficult. The general’s guards and Gudreka nodded to each other as he passed. He found his general lounging on a metal chair that folded on hinges for travel, a silver goblet of mushroom brandy dangled between his fingers as he was being dotted upon by the prostitutes he hired as servants. Therog was the only soldier of Drenia here with women. All the other dwarves had to leave their wives, wenches, and strumpets behind when they volunteered.

“Ah, there y’are Mud-Vein. Took you a bit, eh?” Therog laughed.

“My General,” Gudreka bowed.

“Out with it, Mud-Vein! Where are those scouts?”

“They’ve returned. They ran off the sentries. Adyrnaarn knows we’re here, my general,” Gudreka said, dropping to one knee and planting his fist on the ground.

“Well and maybe if ye’d been artful on it, we’d have those sentries in hand and them none the wiser,” Therog scolded.

Until Adyrnaarn changed out the sentries in a day or two, Gudreka though. But there was no point in arguing. Gudreka knew his general knew that. It was about–

“What’s the hold up on the siege?” Therog asked, swirling his brandy. “And get up.”

“Water, my general. I’ve tasked the quartermaster with setting up a relay for water from the last stream and the engineer to give a choice on how to get water closer,” Gudreka rose as he answered.

“Hm,” Therog found something interesting in the depths of his goblet and eyed it. “What banners did the scouts see? What’s the senior one?”

“The King’s banner, my general,” Gudreka said as his eyes drifted up the skirts of Therog’s serving women.

“The King’s!?” Therog lurched forward in his chair, the goblet clanged to the ground in his surprise, “with the axe? What’re we waiting for? I want those rams up now and assembled!”

This was what Gudreka had feared in this conversation.

“My general, going at the gates right on outs the boys in a bad way. We can get the city in a better way if we tunnel–”

“–Tunnel!? That’ll take until the next flood! No! Rams up now, Mud-Vein! Get those rams up before the water!” Therog bolted to his feet and leaned towards Gudreka as he bellowed.

“My general,” another voice approached. It was Therog’s war wizard, Aemzon. Aemzon was an older dwarf with a fine lizard-hide coat inlaid with silver in blocky patterns. He was bald and his beard stretched down to his belt. The very bottom of the beard had a faint color of brown. “Listen to Gudreka, eh?” he walked with a limp as the guards admitted him. “Think on the tunnel, eh? It’ll save a lot o’ the boys.”

“Save the boys? What’re we supposed to be doin’ here? The Aedon king’s right there! King Naurom’s right on the other side o’ that gate! You want us to dig a tunnel?” Therog demanded.

“The king won’t leave his people, my general,” Gudreka said.

“Nor will they be leavin’ him! Bust the gate, we fight the city, their king, and the king’s chosen. Dig the tunnel an’ we fight that an’ whatever legions show up, too. Dig a tunnel an’ we give time to the Aedons to raise more legions and move ‘em,” Therog challenged.

Dig a tunnel and save lives while Kurelig gets to Ezkaarn first, eh? That’s what this is about, ain’t it, ya turd skid? Gudreka glowered as he drew a deep breath, “very well, my general. We will bring down the high gate and flush them out.”

“And the low gate, Mud-Vein,” Therog poked Gudreka in the chest with a thick finger.

“… We’ll be losin’ a lot of boys goin’ through two kill boxes, my general,” Gudreka said levelly.

“An’ what’re we supposed to be doin’, Mud-Vein? You’re bein’ so kind to the boys, maybe you want to be their woman and serve them brandy and other things, eh?” Therog spoke into Gudreka’s face.

“Eh, my general, maybe I could be makin’ a stone creature with a scroll. That’ll help the boys get through the kill box and crack the gate. I could maybe make two of ‘em?” Aemzon suggested.

Therog’s body and head reeled over toward Aemzon, “I say ‘no tunnel, it takes too long’ and you say ‘how’s about something else that takes a long time?’ What do you two not understand?” Therog demanded incredulously. “How’s about you,” pointing at Aemzon, “go figure out what you can do to help the rams crack the gates? And you,” Therog stabbed a finger back at Gudreka, “how’s about you get those rams up, eh?” Therog looked between the two of them as they both looked away from his gaze.

“Right, then GET OUT!” He yelled at them. Aemzon scurried with his limp. Gudreka left at an even pace.

“Girl! Come here an’ sit,” he heard Therog’s voice recede behind him.

Typical, eh? Gudreka glowered and then sighed.

“Rangli?” Gudreka called, the fatigue was pouring into him suddenly. “Rangli?” he called again.

“Uh, yes, major captain?” Rangli answered after a bit of searching in the camp.

“Go and fetch me the quartermaster and the engineer again. New plan. Need the rams up soonest,” Gudreka said.

“Uh, yes, major captain, but what about the water?” Rangli asked, his feet shifting uncertainly.

“Rangli. Just go and get them, eh?” Gudreka said.

***

At the entrance to the kill box cavern outside the High Gate of the Dwarven City of Adyrnaarn

By the Dwarven Calendar, 130th day of the 10484th Year

By the Human Calendar, Restday, 1st week of Darri, 794

Another loud clang echoed in the tunnel, another inward dimple showing on the broad thick shield hanging from the front of the ram frame.

“Push boys!” Gudreka bellowed over his shoulder and looked through the narrow slit in the shield. “Almost there, boys! They can’t stop us now!”

CLANG

That one hit the shield right by Gudreka’s head. His ears rang after the echo subsided.

“Push!” his ears still rang. He could barely hear the grind of the wheels of the ram frame on the stone floor of the tunnel. Faintly through the metal-on-stone grinding, the sweep of the oil brush on the bottom of the front of the frame made scuffing sounds with each push on the frame. He could not hear the grating and jingle of the chains as the body of the ram bounced in the frame. The ram was made from a huge, hollow bronze tube, filled with lead and capped with steel, suspended from chains inside the frame of steel and mounted on spoked bronze wheels. These dwarves had been pushing this ram up the slope of the tunnel road for three days under the bombardment from the great siege crossbows guarding the gates, hurling their long bolts of steel, but the worst was about to come.

They were about to push the ram into the cavern by the High Gate. Like any city, the approach to the gate would be covered from many different places where the defenders would shoot their crossbows at the ram crew from the sides. The crewed siege crossbow would continue to bombard them all the way up to the gate. The shield on the ram was barely enough for the attacks from the front, but the sides were unarmored to keep the ram frame lighter over the great distance to push it. More armor on the sides now was not a possible solution the way it might have been for the other crews going on a downward slope to advance on the lower gate.

“Put the stop on, boys! Fresh crew! Double crew! We need to push fast. Hear? Ready with the shield bearers,” Gudreka called. That was the answer. Push the ram through as fast as they could and take the losses. Ranks of shield bearers followed the ram and would chase the ram crew, trying to protect them from flank shots. Gudreka wiped away the sweat from his eyes as the crew of exhausted dwarves let two crews take the load of the ram. Gudreka looked over them. Most of them were young with short beards. Most of them were barely over forty floods old, he guessed.

“Right, boys. This is it! We’re gonna push this ram and make it rumble like the deep stones. We’re gonna break this here gate! And we’re gonna bring honor upon ourselves, eh?” Gudreka called to them. They panted from the exertion of taking over the ram. They were rested, but by no means were they fresh. They had been on the same grueling push over the last three days and that was after the march here from fighting in Kandaneria. But he could see the light in their eyes. The fervor. They would return Drenia to glory. They had the will to fight. They were young and the young were always the most eager to fight.

“Ready, boys? Ready,” Gudreka watched their faces harden as they steeled themselves. “GO!”

The dwarves gritted and braced their bodies and pushed with their might. Gudreka pushed against the frame as well. The ram frame slowly lurched into a faster motion. They were still pushing the ram up the slope. The air cleared a bit as the frame pushed past the mouth of the gate cavern. The kill box. A fresh breath was all they got before the air was thick with buzzing and pinging and clanging of the crossbow bolts and the acrid smell of oil on the ground. The defenders were shooting them from the sides and the ram crew took them. Gudreka felt the air sear past him from one and jerked to the side, stumbling, as another glanced off the edge of his plate pauldron. Some of the ram crew were lucky like Gudreka, others not so lucky.

Yelps of surprise and howls of pain sounded behind him. The hurried shuffle of feet of replacement dwarves blended in with the steady clop of the remaining crew. The shield bearers squeezed between the ram frame and the tunnel wall, out into the kill box cavern. Their broad, tall steel shields dragged and skipped on the ground as they rushed to their task. The shield bearers on the left moved faster than those on the right. The crossbows of the high gate of Adyrnaarn claimed some of the shield bearers on the left as they rushed into position and the defenders on the right shot at the crew, some bolts missing the crew and finding the backs of the shield bearers on the left.

The wounded and dead lay on the ground as the rest of the crew pushed the frame past them, stepping over their fellows who feebly reached for help. The crew and shield bearers that rolled on the ground, crying out in pain were soon silenced by the defenders, sprouting a bolt or two from each of their bellies as if they were dirt mounds spawning metal mushrooms.

“PUSH, BOYS!” Gudreka’s legs burned in the push as the frame creaked forward. More shield bearers moved up and the crew was mostly protected. The bolts from the defenders sounded against the tall shields much like the sharp fragments of rocks bursting from heat. They pushed and strained as they creaked across the cavern floor towards the doors to upper Adyrnaarn. Maybe it was for a few minutes. Maybe it was for a few hours. Gudreka could not tell how long, but it seemed an eternity, where his boys sweated and died while that buffoon Therog sits in safety and runs his greasy hands over his whores.

TANG.

Gudreka’s world flashed white and spun as he slammed to the ground. His ears rang. He could not hear anything at first. His vision was blurry as he crawled to his hands and knees. He could hear the blurt of voices. It was not the first time the Gudreka had taken a hit to the helmet, but it was always a hard hit when a bolt slams into one’s own helmet. Gudreka was glad the helmet was still there. The pain in his head warred with his concentration and he knew his neck would be dreadfully sore in a bit. If I can manage to live through this.

“RIGHT BOYS! PUSH,” Gudreka felt the vibrations in his throat more than he could actually hear himself over the ring or distinguish any particular sound over the muffled, distorted cacophony of dwarves’ shouting voices and metal striking metal. He squinted through the small aperture in the front shield plate of the ram frame. They were almost to the gate, now. He chanced a glance over his shoulders. Only a couple dwarves of the crew that started the big push were still on the ram frame. The rest were replacements and he could see the unmoving silhouettes of bodies in the trail behind the ram frame.

“PUSH, BOYS! A LITTLE MORE!” Gudreka called. Light caught in the corner of his eye. His sight darted over to it. The cavern was lit by flaming braziers, but this was a new light. A light in the stone slits that the defending crossbows shot from. Gudreka closed his eyes as more lights appeared in other slits. This is when they bring the fire. They must’ve wanted to beat us before this. Or maybe, they this is where they push back the hardest.

“BURN ‘EM DOWN!” Gudreka heard one of the defenders shout. It was a woman’s voice. Before the war, Gudreka had heard that the Medrians and the Aedons gave weapons to their women, but he had not believed it until the first battles in Medria. Gudreka felt bad at first, axing down women, but they fought, so they died.

The tiny flames leapt down to the ground in the cavern or pinged off of the ram frame. The bolts landed and the ground steamed and smoked for a few breaths before flames leapt up and raced around. It was as if the ground came alive. The flames spread all around the cavern. The smoke choked the air. The ram slowed a bit as the crew struggled for breath, but they were almost there.

Gudreka was thankful for the brush on the bottom of the front of the ram frame. The brush head scraped against the floor and was shaped like a wedge, pushing the oil off to the sides. Gudreka and the engineer had started insisting on this right before their march on Kandaneria because the Medrians did the same thing and they had lost a lot of good boys from being burnt to death. The thin slick of oil that remained smoked, but their feet stamped out the flames as they pushed on. No good for the shield bearers, though. Their boots were soaked in the oil and readily lit when they fire came to greet them.

Their tall shields slopped into the flaming oil as they clamored around and screamed as they burned. One by one, they would slip or stumble and fall into the burning oil, rolling and writhing as the fire ate them alive. The only, only blessing was the fire made it too bright for the crossbows to aim accurately. The ram frame had made it, finally, to the last few paces before the doors of the high gate of Adyrnaarn.

“STAND CLEAR!” his throat vibrated. He was not sure if they could hear him, but they looked. He snatched a hammer from one of the crew behind him, as another one of the forward crew members drew one from his belt loop. They hammered at the retaining pegs for the forward shield. They were close enough to the gate that defenders’ great siege crossbows could mark them and the other crossbows from the side slots had shots on them from the flanks, not the front. The first pair of pegs came out and they feverishly hammered at the last two before casting the hammers aside, lost in the inferno surrounding them, and pushed on the plate. The plate, free of its retaining pegs, rested only on two small shelves on each of the front legs of the frame. Once it began to tip, it carried itself, splatting down into the burning oil slick. Burning globules sprayed in the air, coating Gudreka and the other crew member. The other dwarf hollered, clawing at his face, stumbling blindly into the fire screen. Gudreka grimaced and tried to ignore him and all the other torment around him as his kicked the oil brush off the frame before throwing his shoulder against one of the legs of the ram frame.

“LAST BITS, BOYS!” he hollered as the frame once against skidded into motion. They strained and grunted as the brightness of the flames and acrid smoke concealed them from the defenders. Gudreka and the remaining crew strained and pushed until the ram frame thudded against the door.

“MORE CREW!” he shouted back at the cavern opening. He had enough to move the ram, but he knew that they would not last. They were exhausted and some would still be taken by the crossbows. Gudreka wanted fresh men right there for when the gate cracked.

“ALRIGHT, BOYS, GRAB IT. ONE. TWO. THREE. PULL!” Gudreka and the rest of the crew grabbed the handles or the chain shackles on the massive bronze ram body and collectively pulled it back on Gudreka’s sounding of ‘three.’

“PUSH!” Gudreka shouted and the group pushed on the ram. Most of its power was in its weight, though. Its weight swung on the chains and slammed into the doors for the gate. It was the first sound that Gudreka was sure he actually heard since taking the bolt in the helmet, though he felt it too. The stone underfoot shook with the vibration and dust puffed off of the door.

“GRAB IT. ONE. TWO. THREE. PULL!” the crew repeated the drill and pushed the ram on Gudreka’s command. Again and again, they pulled the ram back and pushed it, offering a tiny addition to the mighty weight of it. They heaved with exertion. The metal of the high gate strained and screeched like a dying beast of the deep. Sweat mixed with the soot from the burning oil to make a greasy, ashen mud caked to their faces and slide down their bodies.

“PUSH!” Gudreka bellowed. A thunderous twang echoed as the warping metal snapped and gave way. They had slain the spirit of the high gate. Or rather, half of it. One of the doors slammed against the interior wall of the gate house and fell off of its hinges, shaking the ground with another loud clang. Beyond it was the interior gate house and another gate. Overhead wer murder holes for the defenders to rain all kinds of unpleasantness upon them. Gudreka braced himself for more death to stare at.

“PUSH, BOYS! ONE MORE GATE AND YOU TAKE THEIR WOMEN!” the men cheered behind Gudreka as they pushed the ram frame into the gate house. The frame had a roof of steel sheets, but it was thin. Large rocks panged off of the roof and crossbow bolts pinged off, making divots or poked through. A few penetrated the roof and clanged off of helmets or pierced the mail on the necks and shoulders of his men.

“PUSH!” they repeated the drill, pulling the ram back and pushing it forward. The inner gate screeched in agony as Gudreka heard the thick patter of liquid hitting the roof of the ram and pouring off of the sides or dripping through the holes made by the bolts.

“MORE OIL! PUSH BOYS! THEY’RE GONNA TRY AND BURN US AGAIN! PUSH IF YA WANT THOSE TASTY TREATS ON THE OTHER SIDE!” they pushed again, but light flared around them before they could pull the ram body back again. Hollers and screams of men burning alive sounded behind him as the ram lost the strength of so many men at once. It weakly nudged the gate, slightly torn ajar.

Curses! Gudreka looked back. There were more men rushing into the gate house, but he needed their strength to fight on the other side of the gate, not to spend it on the ram. The men whose strength should have been spent on the ram was being eaten by the hungry fire. Gudreka coughed and choked on the smoke before blowing it out through his mustaches.

“LET’S GO, BOYS!” he shouted. This was the best way because it was the only way. Hustling past the capped head of the ram and pulling his fighting axe free of its belt loop, he squeezed through the gap between the doors where they had started to give. Two more hits and the gate would be done, he lamented, but this was the only way. Spears immediately demanded his lifeblood as they coursed for his neck and face. Sweeping them aside with a reflexive whirl of his axe, he pushed the spear shafts up can kicked one of the defenders while fresh men squeezed through the gap behind him. The first two gave their lifeblood to the indignant spears of Adyrnaarn, but more came. Gudreka fought for his life for a few moments, barely keeping speartips and axe blades off of him, sometimes slapping them aside with a gauntlet. But as more men entered through the gates, they took the fight from him.

Gudreka stepped back and bent over, heaving for breath. The air inside the upper gate garrison cavern was much clearer since there was no open fire trying to claim anyone in there. He was vaguely aware of more dwarves rushing through the gap in the gate and some of them prying the rest of the gate open. The light of the fire from the gate house and the kill box cavern washed over him and danced in the shadows of more men flooding into the high gate. Soon the twang of defending crossbows silenced as Gudreka’s men silenced those who had been feasting on Gudreka’s flanks for so long.

He pushed himself off of his knees and stood up “FORWARD, MEN!” He walked more casually now. The worst was over. There was a great deal to do, but they were inside the high gate, his main force was flooding into the high gate garrison, and the defenders would not be able to tell that the push on the lower gate was a ruse.

He stopped in his tracks as he saw a pair of his men pulling one of the defenders down and stripping their armor off. He already knew the situation before he came upon them. One soldier was holding the defender down while the other one was working on his trouser belt. Gudreka kicked the man over that was working on his belt.

“OI!” the belted man angrily yelled before realizing it was Gudreka. “Oh, Major Captain, eh?”

“FUN LATER. FIGHT NOW,” Gudreka shouted firmly.

“Eh, boss, it’s just a snack to keep us going,” the other one protested while the defender soldier, a woman, writhed and screamed curses at them in the Aedon tongue. Gudreka drove that spike on the butt end of his axe shaft through the ribs under her collarbone. The light in her eyes died with surprise.

“OI!” the other man leapt back from holding her down. Gudreka held the axe threateningly at the belted man and then slew it over to brush near the other man’s face.

“Fight now. Fun later,” he said again. He did not shout this time, but he was firmer. The two men gulped. “Aye, major captain,” they said.

***

Upper levels of New Adyrnaarn

Hrene grabbed a young dwarf newly draped in the livery Adyrnaarn, “you! Go report to the major captain that the garrison is lost to the Drenians.”

He stared at her wide-eyed, “but-but-” he stuttered.

“Captain,” she supplied.

“Captain-cap-c-” he stuttered more.

“Captain Hrene,” she helped more, gripping him more, starring into his eyes meaningfully, and spoke loudly and slowly, “I need you to tell Major Captain Havrali that Captain Hrene says that the Drenians are inside the city. We have lost the upper garrison completely and they are coming into the city. Do you understand?”

The young dwarf starred at her for a breath and she was about to shake him again when he nodded and scampered off towards the closest stairway.

She climbed up some steps to the one of the halls on this level, so she could see out over the heads of her soldiers as they clamored into positions near the mouth of the tunnel to the high gate. Stone walkways hugged the perimeter of the cylindrical cavern that was the largest space of Adyrnaarn. Water fell from a hole in the ceiling of the cavern and fell the length of the cavern to supply the reservoir at the base of the city. More water trickled in from a smaller stream a few levels beneath them, creating a gentler waterfall over the lord’s halls section of the city. The lights of the city glistened off of the falling water, making it sparkle.

The soldiers formed ranks across the entirety of these walkways on either side of the large opening of the tunnel. In the upper floors and balconies of this level and further parts of the walkways, she had positioned her crossbows, so as to strike the invaders from all sides as soon as they tried their way into the city proper. How could we have given them the upper garrison so easily? She berated herself internally.

“Alright, you broad axes and bright spears!” her voice carried over their heads and echoed off of the ceiling of the cavern. Some of their heads turned toward her, but most remained fixed on where the enemy would emerge.

“This scum’s the worst of all dwarvenkind. They take children as slaves, turn proud women to whores, and throw the men to the mines alongside their goblin slaves an’ work them to death! YOU’re the bulwark. YOU’re what keeps their base kind at bay. YOU’re the king’s shield! No matter how many o’ that filth come through that tunnel, you give ‘em a chop in the throat or a poke in the eye an’ let the ranks behind them see what we’ve got for ‘em. When there’s too many o’ them dead on the ground, give ‘em a toss over the side.”

There were no cheers. They all had a grimness about them. They knew that many of them were about to die.

“They have no golems wit’ ‘em,” Hrene continued. “They puttin’ nothing but flesh forward here. Give ‘em enough pain an’ they’ll fold.”

A loud, metallic clunk echoed from up the tunnel. That sounds like, Hrene was thinking just before a blur of motion smashed into the ranks at the tunnel mouth, sending the bodies of six dwarves spinning over the side of the walkway, plummeting into the depths of the city. Some of them screamed as they fell, but one of them had a large steel bolt impaling its body as it sunk to the depths with no sound.

They’re using our own siege crossbows from the gate, it registered with Hrene. “CLEAR THE TUNNEL PASSAGE” she tried to contend with all of the noise and panic as the soldiers already were already scrambling away from the entrance to the city, pushing back against the ranks that had formed behind them. The Drenian soldiers came after that and fought a bloody stalemate for a long time. The wounded and dead from both sides piled on the walkways or fell over the railings. The upper levels had already been evacuated and everyone pressed into arms that could bear axe or spear, but the Drenians kept coming. Adyrnaarn was not a big city and it seemed the Drenians had brought enough to pay in blood for all of them.

And they’ve got a wizard, Hrene remembered from one of the briefings from the days before the Drenians broke the upper gate. One of the king’s spies had gotten a message through before the Drenians arrived. They had a wizard and it was only a question of when the Drenians would put him forward. What kind o’ person is that? She wondered. Spies were widely considered a dishonest and dishonorable profession, yet Hrene was thankful for every bit of information that they had provided before the Drenians closed off the upper and lower gates. An’ that’s another thing. The Drenians were still pressing on the lower gate and they could put all of the king’s legion against the high gate in case they broke the lower gate.

Hrene had come with the king’s own legion to reinforce the homeguard of Adyrnaarn and, the king had hoped, throw the Drenians back at the gate, break their momentum and drive them back through Kandaneria. But there’re so many o’ them for all o’ the spies the king had big beats small. ‘Specially when they haven’t shown their wizard yet.

Bit by bit, the defenders of Adyrnaarn, homeguard and king’s legion alike, had to give ground and the Drenians controlled the upper levels of the main city, enough so that they wheeled down the siege crossbows from the upper gate and began bombarding the defenders, forcing them to give more ground.

Their defense concentrated around the great stair, a spiral of stairs, smooth ramps, and a central shaft for a cargo hoist that connected most of the levels to together. There were other stairs and ramps around the periphery of Adyrnaarn, but they were small and could be help by a smaller number of defenders. They were losing another level of the great stair, suffering losses at every level where the entrance to the great stair could be scene and angled by the siege crossbows on the higher levels, when the young dwarf from hours before, his scant beard struggling to break through the skin of his face ran up, stumbling to a stop and panting for breath.

“What?” Hrene demanded irritably. The boy-dwarf held up a rolled scroll for Hrene, leaning on a knee with his other hand. Hrene took the scroll and unrolled it. Finally, she grumbled. She shoved the scroll back at him, “you tell them not to wait. We’ll be getting’ out o’ the way when they come.”

The boy-dwarf ran off, squeezing his way through the defenders and down the great stair to deliver Hrene’s reply. They were too many levels below the top for the stolen siege crossbows to bombard them, so they could openly fight on the great stair. But because Aedon fought openly on the great stair, so did Drenia, and right then, the line was buckling at the left flank. Two, three ranks were folding, dead and dying laying at the feet of the Drenians as they started to press the king’s soldiers on two sides.

“C’mon!” Hrene strapped her shield to her arm and snatched her battle axe out of the loop as she ran, shield in her other hand. She always had a few soldiers out of the line for just this kind of thing. Tried and tested veterans. Their feet pounded on the paving stones, plates clanging against the rustling jingle of the mail, felt more than heard over the din of fighting. Hrene’s first overhand strike took a Drenian soldier by surprise. He was mid-thrust with his spear and working his weapon over the shoulder of another Drenian. Her axeblade came down on the gap between his pauldron and his helmet. The blade did not break the mail, but it jolted him to the ground. She raised her shield in time as a Drenian axe blade skittered off of it. Her soldiers behind her crashed into the other Drenians as she stepped on the weapon arm of the one she had lain prone and drove the top spike into his open-faced helmet.

He feebly clutched at the axehead as she pressed it in. He shuddered and twitched as she pulled the spike out. The soldier fell limp, but she had already moved on in the space of two breaths, driving the butt spike of the axe between the plates of the Drenian axeman who had been protecting the spearbearer she just killed. The spike passed between the plates and parting some of the rings of his mail. The spike did not drive deep, but the axebearer still fell and her own soldiers finished him off. Holding her shield high, her shoulder tensed and she felt a pop in the joint as the axe squarely rang on her shield. Sweeping widely with the hook-end of her axe blade, it passed until she hit the ankle of another Drenian soldier. Pulling hard, she brought him down and used the momentum of the pull to swing the hook end around and bury it in the Drenian’s chest. The outrage of being killed by a woman showed on his face as he lost the strength to hold up his head.

Hrene and her soldiers beat back the Drenians for a few moments and were restoring the right flank when someone called to her.

“Captain! The golems!”

“Finally,” she called back. Then to her soldiers, “Make a hole! Golems! Make a hole!”

The rear ranks looked back and saw what she was seeing. Massive bodies, four of them, like a dwarf but three times the size, made of stone and clay, climbed the stairs in great, lumbering strides. Two robed dwarves trailed them, shouting at the earthen creatures and waiving their arms as they scurried. These would be the king’s wizard and the wizard of Adyrnaarn. Hrene had never met Adyrnaarn’s wizard and never gotten to know the king’s wizard. There had been no need.

I’ll buy them both drinks everyday for the next three floods if they can pull this out of the fire, Hrene thought hopefully as she shouted for the soldiers to get out of the way. The Drenian’s pace of fighting paused as the golems came into their view. The front ranks of Aedon soldiers had not parted yet when the first golem reached over their heads with a huge hand of living stone and grabbed one of the Drenian soldiers. Its enormous hand easily wrapped around the soldier, armored and thick in belly and all, raised the feebly flailing dwarf over its head before smashing him to the ground in his closed fist. Blood and bile squirted from the lump of flesh hanging in the golem’s hand before it through the heap of gore into the ranks of the Drenians. The ranks parted and the other three golems joined the first, crushing, smashing, picking up Drenians and using them as weapons against the other Drenians or throwing them off of the walkway to plummet to the bottom of the city cavern. The Aedon soldiers followed and mopped up the flanks, eliminating the pockets of Drenians that the golems swept past and finishing off the wounded Drenians.

As quickly as they had lost them, the king’s legion was taking back the levels lost to the Drenians. After retaking a fourth level, the siege crossbows the Drenians had taken from the high gate could manage the angle and began bombarding the golems and the Aedon soldiers with them. One of the golems took several direct hits, with one long steel bolts from the first hit lodged in its torso and the other two hits taking one of its arms. Despite this, the soldiers of Aedon, the two wizards and their golems were able to fight past the entrances to the great stair on each level and managed to lose only a few soldiers to the siege crossbows each floor.

The golems mauled and crushed the enemy in their march up the great stair. The two wizards drove the golems and Hrene’s soldiers hurried to keep pace, protecting the wizards from the few bypassed Drenians. Hrene looked down at the remains of a Drenian as she kept order behind her soldiers. The ruin of a Drenian oozed on the stairs. One of the golems had stepped on him. The legs and one arm were the only pieces easily recognizable. His other arm, head, and body were mashed together with bits of crushed metal and his clothing in a wet pulp that someone would have to clean off later.

Hrene grimaced. They were almost up to where they had been hours earlier: three levels below the top of the cavern. The golems were making great progress, but it was only a dent in the Drenians’ numbers. What was actually important was luring out the Drenian wizard. Ruin enough of their gains to force him to commit. Once they can flush him into the open, the two Aedon wizards can crush him and then commence grinding up the rest of the Drenians.

Flying rock fragments pelted against the wall, sprinkling Hrene and the soldiers with dust and sharp stones. Shielding her eyes, Hrene peered back towards the great stair. The two wizards were arguing. Three of the golems were continuing up past this level’s entrance to the great stair, but the fourth golem, had broken into pieces from the siege crossbows on the high levels. A pair of tenuously attached legs stumbled around, trying to find footing to continue the march upstairs. Hrene could not hear what the wizards were arguing about over the sound of the fighting and shouting of hundreds of dwarves and the rampaging golems, but one of them seemed like he had made up his mind about something.

No, no, nono, “No! NononoNONONO!” Hrene tried to make him hear over the noise once she realized what he was doing. She watched him produce a wand from the folds of his robe. Energy crackled around the tip, forming into a fiery bead. The bead grew into a ball and shot upward, growing in size and brightness. The flaming ball shot past the siege crossbows, impacting explosively on the wall behind them. Mangled wrecks of the siege crossbows, mangled bodies of the Drenians, and bits of shattered masonry quietly fell from the great height to the echoing sound of the boom.

“Now ya’ve gone and done it!” Hrene shouted at him, but she was drowned out by the answering impact. Dust, shouting, and blood were everywhere. Hrene could not see clearly.

“Fight on! Keep ‘em on the run and throw ‘em out of the gate!” Hrene shouted and took the line herself amid the confusion. This was the opposite of what was supposed to happen. The golems were supposed to make the enemy wizard show himself, so our wizards could crush him. The smoke and dust cleared a bit as she fought alongside her soldiers, hacking at silhouettes in the dusty haze that shouted with different accents. Sure enough, she saw the corpse of one of the wizards, half of his face charred away. Two of the golems stood dumbly with no one to drive them. The other wizard sheltered in the arch of the great stair, peering around. Hrene fought on with her soldiers and the other two golems. The were moving up around the broad spiral, when a light flashed behind her and she heard a thunderous crack behind her.

Looking over her shoulder, she saw one of the golems still standing dumbly. The other one was a smoldering pile of stone and baked clay. As she was turning back, a searing light burned a line in the edge of her vision as the Drenian wizard destroyed the other idle golem. The Aedon wizard, close behind Hrene, cursed at the enemy but his voice was drowned out by the din. This was Adyrnaarn’s wizard. She knew because she did not recognize him.

They reached the entrance to the next level from the great stair. The golems, oblivious of any danger, continued to smash and drive the Drenian soldiers. They were breaking from a withdrawl into a rout, even with only two of them. Invincible titans to their puny axes and spears. They ran, but the golems easy kept pace with them, crushing and maiming or hurling them to fall the screaming height of the cavern. Until, they crested the archway of the entrance.

The golems moved ahead of the soldiers and definitely ahead of the Aedon wizard. Another bright, searing light and one of the golems exploded into a rain of rocks, pebbles, and burning clay. Hrene only heard a ringing. The rest of the world was muffled and so it barely registered a sound when another bolt of energy destroyed the last golem. The soldiers of Aedon paused, as did the Drenians. The tide could go either way.

“Fight on!” Hrene cried. She could not hear herself over the ringing in her ears, but she pressed on and the soldiers followed her. They pressed the Drenians past the archway and continued to drive their rout up the stairs. The Aedon wizard clung to the edge of the covering archway. Hrene was barely aware of him. She could not spare anything for him. She had to lead her soldiers with her own axe.

Scorching air and concussion knocked her forward onto the stairs. The helmet took much of the impact, but she could feel hot blood trickling down the side of her face. Pushing herself to her feet, she spared a glance behind her. The wizard and a dozen soldiers lay smoking and unmoving.

Oh, no… she stared at them wide-eyed for a moment. She shook herself and turned back to the only problem she could do anything about, but the tide was already turning. With no golems to crush them, the Drenians were realizing that they still had more soldiers than all of Adyrnaarn and began to press them back downwards. Time always passed surreally in long fights. Hrene had no idea how long she fought, but she knew that the Drenians pushed her soldiers all the way back down. She distantly puzzled as to why the Drenian wizard did not lay into them, having killed both of the wizards on her side. But, she and her soldiers were allowed to live, at least by him. The other Drenians, however, were eager to pay back the pain dealt to them by the golems. They took no prisoners, except for the women. Of the soldiers that got separated from the main line, they threw the men over the side. The soldier women, they stripped them bare and carried them into one of the evacuated halls. Hrene bit back bitter tears as she fought and commanded her soldiers, their numbers now ever so precious, as she did her best to withdraw them to the lower levels.

They fought down to another level on the great stair when Drenians poured in from that level and began rolling up the flanks of Hrene’s soldiers. They must have finally gotten down one of the other stairs. Hrene’s force split. Most continued fighting a withdrawal down the great stair, but without their leader. Hrene and a hundred or so of her soldiers were pressed onto the walkway on this level. The Drenians pressed them from two sides, one coming down the great stair and through the archway. The other Drenians pressed her soldiers from one direction along the walkway. So, they continued fighting a withdrawal. Hrene had hoped to get to another smaller stairway, but they were blocked from the other side and forced onto one of the many bridges that spanned the cavern. The bridge had made a quicker route across the cavern for merchants and officials that would have normally worked on this level. But for Hrene, it was certain death in front of her as the Drenians pressed her backward across the bridge, certain death from the fall on either side, and a glimmer of hope at possibly finding a stairway on the other side of the bridge before the Drenians came the long way around the cavern behind them.

The bridge was narrow and it gave some of her soldiers the chance to rest on their feet after fighting for hours. Hrene kept at the front. Her hearing was better now, but the ringing was still there. They were almost across the bridge and it looked like the Drenians were not going to cut them off at the rear. Just have to deal with the ones in front then, she grumbled. Her soldiers were getting onto the main walkway on the perimeter of the other side of the cavern when the bridge shook with a blurred motion from below. Another blur and the bridge shook again. Hrene staggered, as did her soldiers and the Drenians.

“They’re bombardin’ the bridge from below! Keep ‘em on the bridge!” she hollered. Hrene’s soldiers fought backwards to the mouth of the bridge, which kept shaking from the bolts of the siege crossbows from below, still controlled by Aedon crews. The Drenians sneers turned into desperate snarls, ferociously trying to fight their way onto the perimeter avenue and save themselves. A bolt thumped the bottom of the bridge. A chunk of masonry broke off. That was all it took. The bridge needed its integrity to bear its own weight. A chunk of that size, half of the width of walkway, and it crumbled. Large sections broke off and plunged. The Drenians scurried. Enough of them had scampered back to the side they started on, but not all of them. Scores of Drenians hurtled to the depths as the bridge gave way. Chunks and sections collapsed. The ground gave way under Hrene, as the mouth of the bridge collapsed. Two soldiers fell with her. Her own fighters grasped to save them, catching Hrene and one of the soldiers. She met the eyes of the soldier that fell. He looked back at her as he descended. His face was grim, but without regret. She wanted to reach for him, but he was already too far and her soldiers hoisted her up. She had lost her axe and shield, but was handed a readily available replacement axe from one of their fallen.

She heaved a heavy sigh, “let’s find us another stair.”

***

Maybe an hour later

Two levels below the Middle Gate of Adyrnaarn

Hrene and two other soldiers burst out of the entrance to the minor stairs, alert and with weapons ready. Echoes of the fighting sounded above.

“Why here, Captain?” one of the soldiers asked.

“Dreadful close to whining, there!” she scolded, “but here’s the rally area that was in the major captain’s instructions. Now get the rest of them down here.” Her knees and shoulders ached, but she stood upright and proud. The will of the soldiers wore thin and would wear thinner before the end. That be where it’s headed. The end. She thought bleakly. Those buffoons, the two wizards, bumbled their last chance to through the Drenians out of the city.

The rest of Hrene’s soldiers piled out of the stairway. About a hundred of them. Most of her soldiers would still be fighting in the great stair, but they were separated. Hrene’s best hope was to reunite with them at the rally area or fight for their relief. But to what end? She stood immediately by the arch to the minor stair. Each of the soldiers seeing her strength, no matter how much she had to prop it up on the inside, they saw her standing straight and straightened themselves passing by her. She waited for them to file out completely.

“Last one,” said a dwarf woman from behind a closed helmet with a dent in the visor.

“Good. Form a column,” Hrene commanded. “We’ll not be walkin’ back a mess. Show ‘em we’re still gonna fight, eh?”

The soldiers meandered, but a bark from one of Hrene’s few remaining sergeants but some spunk into their step.

“Fine, then,” Hrene said and moved off over the bridge across the cavern on this level. It was wider than the bridge they had fought off of on the higher levels. The column should be able to march across five shoulder-to-shoulder. She heard the sound of the column marched behind her, tired footsteps. Soldiers on the march would sing often, but they could not muster the hope to sing just then.

“Sing To The King’s End,” she called over her shoulder.

There was an exhausted silence behind her, only the clopping boots on the cobbling of the bridge.

“You heard the captain! Eh? You filthy worms better make ‘er proud!” yelled the sergeant.

“What. Does. The king. Say?” The sergeant punctuated the words with each step, timing them so the other soldiers could mark their step off of his.

“The king. Says. The orcs. Came. Today,” sounded the soldiers. Echoes of the fighting sounded from above. Now and then, falling bodies of warriors plummeted past them, having fallen from the high levels. Some of the bodies struck the bridge and bounced off, leaving bloody splats on the masonry.

“And. What. Does. The king. Do?”

“The king. Fights. He kills. With axe. And spear. He fights. With. His own.”

“What. Does. The king. Need?”

“The brave. “And. The strong. By. His side.”

“And where. Were you?”

“We were. There!” The soldiers cheered.

“Where?” The sergeant screamed at them. Hrene always liked this song, but found it sadly ironic now.

“We were. There! Atop. A pile. Of broken. Bodies. Green. Skins. With. Dead Eyes. And. More. To come!”

Hrene could hear them cheer on more, their spirit somewhat restored, but she stopped listening. More bodies were falling, but they were not the bodies of soldiers and warriors laden in armor. They were children, elders, new mothers and young father clutching their babes as they careened past. Hrene’s eyes went wide at the rain of her people. She marshalled her face to calmness. That’s the way o’ it. She thought bleakly. Mass suicide of civilians was for when the savages broke the gates, when they were overrun by orcs, hobgoblins, goblins, ogres, trolls, and the like. Death was a better fate then the life of slavery that awaited them. Death was better, guarding the secrets of the craft, rather than let the beasts cut them out of you or worse, force you to perform the miracles of dwarven craft for their own butchers. It was long recorded in the histories that dwarves taken prisoner suffered the worst of fates, being tortured to work, but those that had it worst were not tortured themselves. Dwarven families taken prisoner would have work for the savages or bear watching their children be tortured and killed.

Better this way, but it was normally reserved for the filth. Not… not for other dwarves. But Hrene had already seen what the Drenians would do. Any other Aedon did not trust a Drenian for their word and everyone knew they kept slaves, but Hrene had seen with her own eyes stripping the women soldiers they captured and carrying them off.

Shaking the recent memory from her head, Hrene focused on the work in front of her: get these soldiers to the rally area and get them back in the fight. A short time later, Hrene’s column marched into the marketplace on this level, cleared of the carts and stands. The marketplace was bustling with soldiers and messengers running here and there. The taverns hummed with activity as the king’s legion had taken over its kitchens to feed the soldiers that were not fighting.

“Rest them here,” Hrene called to her sergeant and hurried off to find anyone that knew what was going on. Forcing her way through the crowd, she found the headquarters of Major Captain Turiotli and several of his clerks.

“Major captain!” she called as she forced her way through the crowd.

Turiotli looked up from a scroll her was reading as another messenger was talking to him urgently. He held up hand to silence the messenger. Sweat and nervousness painted the messenger’s face.

“Hrene! You live!” a smile split his face of worn stone and bent his beard of wires.

“Major captain! I was separated from my main unit in the great stair. I–”

Turiotli held up his hand again, this time to pause Hrene. “I know. I had a report on it.”

“I have a hundred axes with me. We’re ready to rejoin the fight, captain,” Hrene said.

“You and yours need to be eatin’ before you’re goin’ anywhere,” Turiotli said.

“But, captain–” she protested.

“–No. Look,” he pointed. Hrene followed his direction and saw tired soldiers in clumps around the marketplace, sitting on barrels or merchant carts or on the ground. The ate soup from bowls or tore meat with their hands and teeth.

“Need to eat to fight. Who wants to die hungry anyways?” he chuckled. “Go and get them fed and come see me.”

Sour-faced, Hrene left the command post, found her sergeant, and pointed him at the nearest tavern with the direction to feed the troops. She watched as the sergeant goaded the soldiers to their feet and marched them. She was almost back to Turiotli’s command post when her sergeant’s hand pulled on her shoulder through the crowd. She half-turned and looked in annoyance only to have dried meat and bread stuffed at her.

“You need to eat, too, captain. Can’t have ya fallin’ over in the middle of it,” he scolded her.

Hrene took it sourly and turned back toward Turiotli’s command post.

“Ah, good. You ate, too,” he said. He glanced up anxiously at the higher levels.

“Where can we fight, captain? Is my main unit still up there?” Hrene asked urgently.

“Chew your food, captain. Finish eating before you rush off to die again,” Turiotli said, wiping the sweat from his brow. His surcoat of the king’s legion was smeared with ash, mud, and ink where Hrene’s own surcoat was mainly colored with blood now. Hrene scowled as she bit off the end of bread that her sergeant had pressed up on her.

“It will be different for ya. King’s orders. You’re to take some soldiers and get the wounded and the gnomes out o’ here,” Turiotli’s head leaned forward to look her pointedly in the eye.

Hrene could not believe her ears, “and run from the fight?”

“King’s orders,” Turiotli tried to quiet her a bit.

“And is the king leaving this city!?” Hrene’s voice rose with outrage. “Where be the king?”

“The king fights in the great stair, captain,” Turiotli said.

“Then I will go an’ fight there, too. Beside the king,” Hrene said and started to move off, but Turiotli yanked her back by the shoulder.

“You will not,” he pointed a low finger at her chin.

“But, you said the rest o’ mine are down here. I take ‘em back up and give it to the Drennies,” Hrene said.

“No, you don’ have anything besides those hundred over there,” Turiotli said, “ya’ve been relieved o’ them.”

“Relieved!?” the words slapped Hrene. How? What did I…?

“King’s orders,” Turiotli said.

“What… what… have I angered the king?” Hrene looked around the floor.

“No. Th’ opposite,” Turiotli said solemnly.

“THEN WHY!” Hrene shrieked in anger. Blinking back tears, “why does the king shame me? Spurnin’ me at the last?”

Turiotli took a breath, “the king trusts you to do the job. He needs the wounded out of here. He needs the gnomes out of here. An’ the siege crossbows on the Middle Gate do no good here anymore. Ezkaarn and Zol are next in Drenia’s path, so take the crossbows there, tell them how the Drenians came at us, and fight with them.”

There argued a bit more, but the king’s orders determined the outcome. Numbly, she shuffled her feet through the crowd back to her soldiers.

“Sergeant Marchag,” she mumbled, her voice lost in the bleak energy of her surroundings. She lifted her voice and called again as she came nearer. “Sergeant Marchag.”

“Captain? Have we orders?” her sergeant bounded to his feet.

“That we do, sergeant. Get them ready. I’ve bad news to bear,” Hrene said.

Sergeant Marchag guffawed, “bad news, eh? Worse than this?”

Hrene nodded solemnly, “worse it is. These orders, I mean.”

***

Upper levels of the Korlaeith section of Adyrnaarn

Two days later

Gudreka watched another slew of families jump to their deaths, plunging from the middle levels of Korlaeith to their death in the reservoir. These Aedons were strange to him. In Drenia, suicide to avoid capture was only when defense from the savages, orcs, goblins, that kind, was failing, mainly to prevent them from torturing secret knowledge from the prisoners. Gudreka was surprised when the first families jumped and was more surprised that it did not stop. Aedon had a nagging feeling that Drenia had underestimated the fighting spirit of Aedon. But today! Today the day is won, he shrugged to himself.

“Rangli!” Gudreka called, raising his voice to boom over the sounds of lingering fighting.

“Major captain! On the way!” Rangli’s answer faintly sounded. Moments later, Rangli trotted up. Spatters of blood flecked all over him, matching Gudreka. “Yes, captain.”

“Tell the minor captains they’re on their own authority to finish up here an’ bring me the trophy. After that, you can help yourself to the prisoners,” Gudreka instructed.

“Yes, major captain,” Rangli trotted back off to carry out his orders.

Gudreka had been putting this off, ironically taking refuge in the fighting rather than face the task ahead. He knew Therog was furious at Aemzon’s intervention, but it was very clear to Gudreka that Therog would have denied Aemzon’s intervention if he had been asked. Ah, well. It ain’t wine. It ain’t gonna taste better with age.

***

Therog’s command post, Lord’s Halls of Adyrnaarn

“That wasn’t your place, either!” Therog shouted, spilling wine from his cup.

“And what was your place, general? Eh? During all the fighting? With your men doing men work or laying under a whore all the while the boys of Drenia be bleedin’ dry and getting’ smushed by Aedon’s golems,” Aemzon shouted back.

“An’ what was the purpose, do ya suppose the king had when he sent me with ya?” Aemzon continued, “do ya think the king’s like, ‘ah, that boy-o there, Therog, needs someone to paint his whore’s nails. Better send him a wizard!’ Certainly not to save the blood of Drenia, eh?”

“Oh, inpretin’ the king’s will is one o’ your skills, now, is it?” Therog retorted.

“High captain Gudreka,” the guard announced. Stone-faced Gudreka entered. He was painted in mostly dried blood and bore a bag over his shoulder.

“Oh, just in time, Gudreka! Maybe you’ve got an eye for the king’s will, too, eh?” Therog baited.

“The fight’s about done, general. Korlaeith’s done,” Gudreka said. Aemzon could tell he was spending a lot of effort to keep his voice even and his face calm. Aemzon knew that Gudreka hated Therog, just as he did himself.

“That’s good an’ all, but how do ya answer for this?” Therog jabbed a finger towards Aemzon.

“How do ya mean, general?” Gudreka asked evenly.

“Oh, don’ play stupid. Aemzon interfered with the fightin’ and took the glory away from the boys!” Therog rounded on Gudreka.

“As he did, the Aedons were goin’ to push us all the way back to the high gate, if he didn’t,” Gudreka said.

“Ah, so ya asked him ta–” Therog hissed.

“The good captain did nothin’ o’ the sort. I took it upon myself to fight. An’ they had two wizards that woulda burned the boys to ashes, too,” Aemzon talked over Therog.

“Ah, so good thing, that I only be needin’ to throw one o’ ya in shackles for disobedience. I get the relief of the other bein’ thrown in chains for incompetence at not bein’ able to crush the Aedons an’ their small garrison. How about–” Therog spat at Aemzon, but cut off as a large object thunked on the floor wetly and rolled at the edge of Aemzon’s vision.

They both jumped. A bloody head rolled on the floor and came to a stop between them. It’s eyes stared up at Therog.

“King Naurom of Aedon,” Gudreka said.

Therog stared at the head for a moment before shaking himself, “if ya think this changes things, you’d be makin’ a mistake. You’re on thin tolerances, major captain!”

“Ya’ve orders, general?” Gudreka asked in a neutral tone, not having moved from where he stood.

Therog glared at Gudreka before he spoke the next words, “you’re to get the boys ready for Ashgar Isriol and be sendin’ scouts to Ezkaarn. An’ no mistakes at Ashgar Isriol,” Therog warned, “we’re to make good time and break the gates of Ezkaarn before Kurelig is done with Zol. Understand?”

“I understand your orders, general,” Gudreka said.

“An’ you!” Therog stabbed a finger back at Aemzon, “since you’re so understandin’ o’ the king’s will an’ takin’ care o’ things, you’re goin’ to… fix the plumbin’… yea, here in the lord’s hall first,” Therog smirked at the end.

“The plumbin’, general?” Aemzon said dumbly.

“Yea, the plumbin’. Work your magicks, master wizard. Begone,” he waived them away. Turning and sloshing his wine a bit more he walked towards he back of the hall. Aemzon knew he was going to the bedchamber of this hall to lay with his whores some more. Aemzon shook his head in disapproval. Never had he seen a general so unwilling to fill his station. His face scrunched in a glower such that he jumped in surprise when Gudreka nudged him.

“We should be goin’, Master Aemzon,” Gudreka said. Aemzon nodded and they both left, quietly passing the guard. The guard nodded ever so slightly to both of them.

“The plumbin’,” Aemzon blustered in outrage when they were at the great stair.

Gudreka heaved a sigh and looked over at Aemzon, “whether you agree with the general’s priority or not, the plumbin’ does not to be addressed to bring this place back into use. I can’t say anything for your decision to fight, but I know ya killed two wizards and I know the boys are mighty grateful. They might give ya some o’ the women if you went by the taverns at the middle gate,” Gudreka suggested. Aemzon stopped walking and Gudreka took a few more steps before stopping and turning back.

“You’re a good man, Gudreka,” Aemzon said. The two parted company without a further word. Aemzon found his way back to his own hastily furbished dwelling. The soldiers in the headquarters detachment had carried in Aemzon’s trunks of books into another one of the lord’s halls.

“Leave me. Take your meals and find your women,” he waived off the staff. The young soldiers smiled and thanked him as they left, but Aemzon was only listening for the receding sounds of their footsteps.

Aemzon pulled a chair up to a table next to his trunk of books, “Ryn. It’s safe.”

A pinprick appeared in the air in front of him and slid, forming a line before the line split and made a whole in the air. A tiny red face peered through before tiny red, clawed hands wrapped around the edges of the hole in space and spread it further. A tiny, slender woman of red skin with wings and horns crept through and stood on the table in front of him. Aemzon gave her a tired smile and affectionately stroked her body with his finger, which was about the same size as her body. She smiled and hugged his finger.

“I dunno if I can keep servin’ the king’s will under this idiot, Ryn,” Aemzon said glumly.

“I see how hard you work, master. I see your brilliance and your cunning,” she kissed his finger.

“I love ya, Ryn. I’m glad we made that contract all those years ago,” Aemzon said.

Chapter 28

A small hamlet, south-west of Serna; west of Keppa

Twosday (2nd day of the week), 1st week of Darri (5th month of the year), 794

Mid-Summer

Overcast and humid

“We have enough problems without your like coming here,” said the headman.

Julian took a long, deep breath, “I understand this is hard, Headman Oris, but the Lord Serna needs your support–”

“–Look here, young man! We’ve already had conscription patrols from Keppa, from Garber, and Yvel, itself! And now, you’re coming here for more!? None of those patrols, AND DEFINITELY NOT YOU, even bothered to keep those scoundrel bandits away when they came through last week!”

“Bandits?” Julian muttered to himself curiously.

“Master Headman, we’re not here for conscription,” Liri began in a conciliatory tone, “we’re looking for–”

“I DON’T CARE! Get off with you! Out!” the headman insisted.

“–volunteers,” Liri finished.

“You don’t understand? Get out. Get. Out. There’s no one left to conscript. Volunteer. Whatever you want to call it. Look around,” the headman gestured to the small hamlet. Liri and Julian stood in what would pass for the hamlet green with six houses around it. The houses were made of clay and straw around frames of wooden planks and sticks with larger timbers to bear most of the weight. The roofs were thatched except for one, probably the headman’s house, had a tile roof. Proof to the headman’s point, Julian could only see very young children and oldsters minding the work and keeping the village running. He could see three farm houses in the distance around the hamlet, but only one field showed signs of activity. This is going to be a very rough winter, he thought bleakly.

“You’ve made your point,” Julian said, turning to mount Pine, his roan mare.

Liri was mounting her own horse when the headman called, “this your own fault for bringing the war here in the first place, Serna!” Julian’s head hung, starring at the ground as he absently guided Pine out of the nameless hamlet.

Liri caught up to him a moment later, “you ready to go back?”

“Yea,” he said plainly. They rode on in silence for a few miles. No sound but the wind rustling the leaves occasionally and the clop of the horse hooves on the hard-packed dirt road. The air was brisk and smelled clean.

“Are you going to take Sir Merik’s offer?” Liri said abruptly. Julian was quiet. More than a minute passed in silence. “Julian?” she asked again.

“Nah,” he said, wiping sweat from his brow.

They rode further in silence for a while until Liri spoke again, “so you’re staying?” Again, Julian was silent. “Julian!”

“Huh? Yea. Staying,” he said.

“So? What is it?” she asked.

“What’s what?” he said.

“Listen. I don’t have time–none of us have time–for your mopey scat. We’ve a job to do,” she scolded.

“Right, tenleader,” he said dejectedly, “whatever’s needed.” They plodded along to the northeast, towards Serna and Keppa, for a few hours in silence until the next tiny village came into view. It was quiet. Julian sat up in the saddle, suddenly alert. Very quiet. He and Liri came to a halt, surveying the area. The nearest house was four hundred or so paces away, but they would have still been able to see movement or maybe hear something. Nothing. Julian looked to Liri and she motioned for him to circle left, to the north around the village. Julian walked Pine on, skirting the village, quietly plodding through the fields. And he saw them. Three, at first. People dead in the fields. Slashed or bludgeoned. A few with arrows in them. He cautiously continued, seeing them, mostly in groups of two, three, or four, the closer he came to the village. He counted twenty-seven, in all. He met up with a grim-faced Liri on the far side of the village. She nodded to him and they walked their horses through the center, seeing more bodies. They exchanged a glance before turning their horses out of town. “They didn’t burn anything down this time,” she commented.

They were most of the way out until Julian noticed Liri starring at something. He followed her gaze. He had to squint for a moment, but he saw it too. Movement in one of the buildings. He looked at her and she nodded. He dismounted and drew his hand axe from a loop on his belt and crept towards the house. It was a small cottage with mud and timber walls and a thatched roof, like most other modest houses in rural Yvel. He crept into the cottage. A few bolts of fabric lying scattered and unrolled around the floor, a few torn or unfinished garments, and an overturned cabinet of thread spools marked this a tailor’s or seamstress’ house. He looked around. He was sure that he had seen something. And then he did. A pair of eyes. Two pairs of eyes. Three pairs of eyes. Fearfully starring at him. They did not look like orc eyes. They were hidden in the piles of fabric with a broken chair on top.

“It’s fine. I’m not here to hurt you,” Julian said. He slowly put the axe back in the loop and held his hands open and in front of him. One of them shuffled. Then another. All three of them stood slowly with two more coming out of hiding from under the straw-mattress bed.

There were two children, both boys, and three adults, two women and a man. “Who are you?” one of them spoke in Eklendan, an adult male with red hair and an Eklendan jaw.

Julian’s Eklendan was not so good, “My name is Julian. I am from Serna.” Julian brought them out to Liri, who was holding an arrow she had collected. “What’s that?” Julian asked.

“I don’t recognize it. Maybe someone else does,” she said, stuffing it into one of the leather saddlebags. They walked and rode back to Serna. Julian and Liri spent most of the time walking with the villagers.

“Greenskins, right?” Liri asked.

“What?” one of the women said, “oh. We didn’t see them. They came at dusk and it was too fast.” They were silent for a while, “do they really have green skin?”

“Yea,” said Julian, “but some have blue,” he added. It took three days to walk back to Serna with them. They would have made it in less than three or four days if they had more horses or a cart and mule and supplies for five adults and two children, but they did not, so they had to forage, hunt, and lay snares overnight. All of those were starting to get scarce with the start of winter. A pair of rabbits and some wild chives and henbit fed them for the trip. The adults, Jana, Sontrin, and Molok, were tailors, but the children had been from other families. Julian and Liri had been out recruiting for the Serna regiment with little luck. Maybe some of them would join, but at least one would have to care for these children that were not even theirs. Lodging would be difficult, but they could be put to work, either in the regiment or with their craft to supply the regiment.

At the end of the third day, the increasingly foreign sight of their home came into view. New buildings had sprouted up where the old burnt down. They were all four-floor buildings, the fifth and last one nearing completion. The ground floor was for craftsmen and shops, but the upper floors were apartments and barracks. The palisade, completed late in the summer was now having a layer of stone laid with the much-appreciated help of engineers and shipments of stone sent by Prince Arnold. Liri took the villagers into the quartermaster’s office while Julian waited outside with their horses. Liri came out a moment later and walked with Julian over to the training field.

The training field was at the base of the hill by the Covendran manor. It had several archery targets set up, sparring dummies, and quintain. The young Serna militia company had reformed into the even younger first company of the Serna regiment, which was drilling on the practice field. They were walking towards the Lady Judane, who was practicing with her polehammer under the instruction of one of the elves. Bierien, he thought. That probably meant that Lord Dareum was also out recruiting. But there Julian peeled off without Liri noticing, dropping Pine’s reins. Julian strode aggressively to put a stop to something as soon as he saw it.

“Just what do you think you’re doing?” Julian demanded. A squad of soldiers stopped drilling.

The tenman, Baryn Kevr’ail, starred in surprise, “what?” Julian roughly reached in, seizing the shortest soldier, ripping off the helmet with the leather veil and casting the soldier on the ground.

“What the scat, Julian!” Ziek angrily yelled from the ground.

“You watch your mouth! You’re too young for this and you know it! Twelve years and a soldier!?”

“I’ll be thirteen in two months,” Ziek he muttered as he got up.

“Julian,” Baryn stepped in calmly, but assertively, “it’s not up to you. The lad made his mark on the papers and it’s his choice. You know the greenskins don’t care how old they are.”

Julian looked past Baryn at Ziek’s sheepish eyes looking away. “A mark on the papers, Ziek? Or did you not mention that?” Julian called.

Baryn slowly turned and looked at Ziek expectantly, “well?” Ziek said nothing and turned further away.

“All right, boy, if you didn’t mark the papers than you’re not in the militia or regiment. Doff all that right there and be on,” Baryn said patiently.

“Don’t see why everyone else gets to fight,” Ziek grumbled as he removed the thigh-length leather coat that reached to his calves and gambeson and stormed off.

Julian watched him go and then stepped to leave, but a hand on his shoulder stopped him. It was Baryn. Tenman Baryn. “Don’t do that again, Julian. You have a problem, you bring it to me.”

“Right, tenleader,” Julian looked at the ground, feeling ashamed at his rudeness. He could not look Baryn in the eye. After all, the man had lost his own wife right in front of his eyes. Julian had no idea how he could still go on. Julian walked away only a few paces before he noticed that Liri was standing not far off, maybe thirty paces, with the Lady Judane and Bierien the elf, holding the reins of her horse. They were both looking at him and Liri had her ‘you made a mess’ face with her hands on her hips. Great.

Liri walked towards him, leaving the other two to resume their training. “Save all of the Gersh, yet?” Liri asked sardonically, “or just the town?”

“The boy’s too young to soldier,” Julian muttered.

“Fine, but next time tell me and I’ll talk to the tenleader. I have to go apologize to Baryn now because, apparently, I’ve got a hot-tempered soldier of my own.”

“Sorry, tenleader,” Julian said.

They walked in silence for a bit before Liri spoke again, “are you going to your family’s farm?”

“No,” he said flatly. Why would they want that? Need another reminder of how Ervan’s dead?

Liri glared at him from the corner of her eye, but they walked in silence. Julian was not sure where they were going, so he just kept walking with Liri and their horses. They passed through the busy town green, turned supply dump, bustling with evening activity. They passed the tall, new buildings. One of them featured a soup kitchen with a small counter that customers sit at. It was run by an oldster, too old to fight, but not so old they he could not offer to soldiers and workers some meat and vegetables in warm broth to ward off the cold gusts of wind and the coming season. They passed Mkaela’s closed up bakery and another row of houses.

“Where are you going?” Liri asked.